| |

|

Blinding Powders & Moonless Battles |

|

'Enigmatic Samurai Text' known as the "Sword

Scroll" has been translated into English

Instructions for 'Successful Nighttime Battles' and 'Recipes for

Blinding Powders'

Written over 500 years ago! |

|

Illustration in a Version of the 'Sword Scroll'

that is Found in the Japanese Book "Solo Kendo"

Illustration may show a 'Tengu' Type of Spirit, Teaching

a 12th-century Samurai! |

Attributed to two elite Samurai, the text says that to be an

effective sword fighter, one must have "no evil in your heart," and the

spirit, eyes, hands and feet must all be in balance.

The scroll warns that even those who learn its numerous techniques can

be killed if they take on too many enemies at one time. "It is best to

err on the side of caution and not enter a mountain road infested with

brigands," the scroll says, adding that "there is a saying that goes, 'a

little bit of military training can be the cause of great injury'". |

The Origins of the Scroll are Mysterious - The text claims

that much of the scroll was written by Yamamoto Kansuke (1501-1561), a

Samurai who served a Daimyo (Lord) named Takeda Shingen at a time when

there was widespread warfare within Japan. Some of the text's words are

also attributed to Kusunoki Masashige (1294–1336), a Samurai who served

the Japanese Emperor Go-Daigo. However, whether these men actually wrote

the words attributed to them is unknown.

Making matters even more complicated, four different versions of the

"Sword Scroll" survive today, their contents having been passed down and

published in Japanese books over the centuries. The text and

illustrations differ in each version, although all four versions also

have a substantial amount of content that is largely the same. None of

these versions have been translated into English until now. |

|

|

The scroll contains instructions on how to create and use powders to

blind an enemy. For one powder, the Samurai must "open a small hole in

an egg's shell," let the egg's contents spill out and then put red

pepper into the egg hole and wrap the egg with paper. "When you are

faced with an enemy, smash it on their face," the scroll says.

A more complex powder uses pieces of a Mamushi (Venomous Snake)

mixed with horse manure and finely chopped grass wrapped within a paper

tissue. "Blowing it at an opponent will cause them to lose

consciousness," the scroll says, adding that this technique "has not

been fully tested."

One version of the "Sword Scroll," which was published in 1914 in

Japanese by a man named "Wakichi Sakurai," claims that the use of

blinding powders can be helpful in a major battle if the attack is

directed at the enemy general.

"Should a large battle then ensue, you should make directly for the

enemy Taisho (General)," the scroll says. "As you and the enemy

combatant ride directly at each other and attack, blow the powder in the

eyes of the opponent," something that will blind the general, allowing a

Samurai to put a joint lock on them that "will result in killing the

opponent's hand," making it easier to kill or capture the enemy general. |

|

|

The scroll contains tips on how to battle an enemy force in a

variety of conditions, including on a dark night, when there is no

moonlight. "When battling on a dark night, drop your body down low and

concentrate on the formation the enemy has taken and try to determine

how they are armed," the scroll says, noting that if the terrain is not

to your advantage, you should "move in and engage the enemy."

Another tactic is "to conceal your forces in a dark space in order to

spy on the enemy."

The scroll also has tips on how to sword fight when attacked in your

house on a dark night, advising a Samurai to use both the sword and the

scabbard. Turn the scabbard "so it is straight up and down, which will

protect you from a waist-level cut from the opponent," the scroll says.

One can also place the scabbard "on the end of the sword," creating a

long weapon that can help one defend and attack when fighting an enemy

in the dark. |

| It is Important to Note - In Japan, it wasn't until after the

unification of Japan under the Tokugawa Shogunate (in 1603) that

books about martial arts began to emerge, before that, everyone was too

busy fighting! |

|

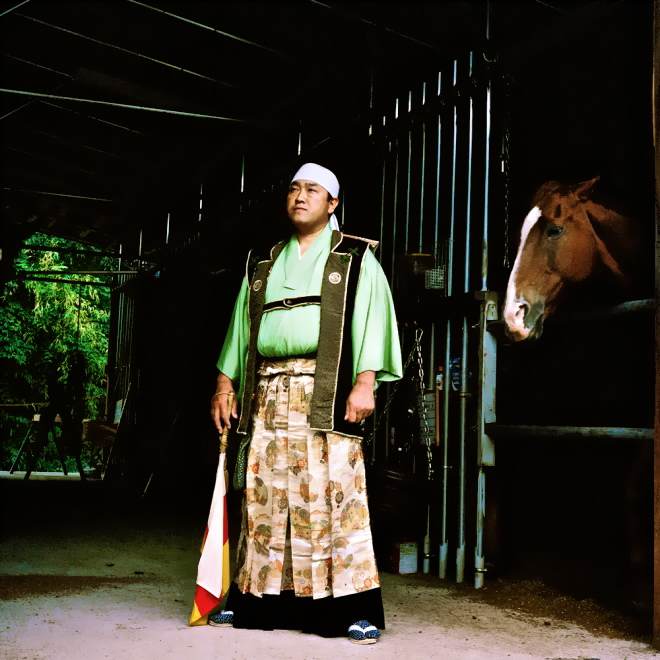

Samurai in Fukushima Guard a

1,000-Year-Old Tradition |

|

Shingo, 34, used to live in Odaka-ku with his family.

Their "favorite house" with an ocean view was washed away 20 meters

inland by the tsunami. Where he stands was once a stable on the side of

the house, now nothing is left but the foundation. "We enjoyed watching

the ocean from this point," Shingo says, "All the belongings including

armor for Soma Nomaoi and two horses that we had taken care of as family

were washed away." |

|

|

|

For more than 1,000 years people of Fukushima Prefecture

in Japan have gathered every summer to celebrate an ancient tradition of

the samurai. The Soma Namaoi festival is as much a part of their

heritage as the warrior and equestrian culture it reenacts and honors,

and in the face of radiation from the nearby Daiichi nuclear reactor,

they’ve decided the show must go on.

The festival goes back more than a millenium to a time when samurai

leader Taira no Masakado started using the area’s wild horses in his war

games. Since then, the event has been held at the Hibarigahara riding

ground and among three shrines in Fukushima, about 30 kilometers north

of Daiichi reactor No. 1. Tens of thousands of people attend three days

of races, competitions and cavalry displays each July, an occasion so

meaningful to the community that it marks the beginning of their year.

Thousands in Fukushima were displaced or saw their homes destroyed when

its residential coastlines were swept away in the tsunami of 2011. Along

with the houses went the accoutrements of Soma Nomaoi — their weapons,

their ceremonial Jinbaori clothing, and, sadly, their horses. Much of

what they’ve worn for the festival since the tsunami is borrowed or

otherwise cobbled together, and after spending months in the vicinity of

the Daiichi plant, many of the clothes they did retrieve, when allowed

to, were likely irradiated. In the Odaku-ku area, a geiger counter

measures radiation between five and 50 times the levels registered

Tokyo.

But apparently none of the people cared about the irradiated clothes. It

was more important for them to have their weapons and their ceremonial

costumes. Despite the radiation they have sustained their determination

to carry out their duty to their culture. This kind of mentality is

still part of the identity of Japanese people today. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Book of Five Rings

by

Miyamoto Musashi |

|

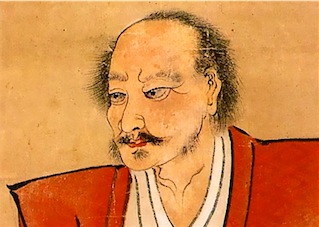

More than three hundred years ago, a legendary

Samurai Warrior named Miyamoto Musashi retired to a cave on the Japanese

island of Kyushu and proceeded to pen what many are hailing today as

Japan's answer to the Harvard graduate school of business.

Musashi, who fought and won 60 duels by the time he was twenty-nine,

called his work "A Book of Five Rings" (Go Rin No Sho). Though it

was written for just one of his pupils, the thin, simply phrased book

quickly became a bible for Japanese military leaders, politicians, and

more recently, businessmen.

Today, Musashi's book has found its way onto bookshelves in the United

States and Europe as Western businessmen attempt to learn the secrets of

their highly successful Japanese counterparts. Reviewed by several

prestigious American business publications, "A Book of Five Rings" has

become an underground best seller in America's business community.

It is not a piece of inscrutable Oriental philosophy. It is, in

Musashi's own words, "A guide for men who want to learn strategy."

What makes Musashi's words as valid today as when they were written in

1645 is that they apply not only to military situations, but to planning

and tactics generally. "A Book of Five Rings" has been used by Japanese

businessmen to plan sales and marketing campaigns, much as a military

commander might draw up a battle plan.

Yet, there is no guide for laying out a campaign anywhere within this

small book. Instead, there are five chapters labeled the Ground Book,

the Water Book, the Fire Book, the Wind Book, and the Book of the Void.

The Book of Five Rings - Excerpts

"A servant must think earnestly of the business of his

employer."

"Even an unadaptable man who is completely useless, is a most trusted

retainer, if he does nothing more than think earnestly of his Lord's

welfare."

"To think only of the practical benefit of wisdom and technology is

vulgar."

"When your thinking rises above concern for your own welfare, wisdom

which is independent of thought appears." |

|

Miyamoto Musashi |

Musashi fought his first duel to the death at age thirteen. He is

known in Japan as 'Kensei' or "Sword Saint".

Musashi was not only an accomplished swordsman, but a painter, sculptor,

calligrapher and musician as well. His ink drawings are among the most

highly prized in Japan.

When he inexplicably retired to his cave in 1643 at the age of

fifty-nine, Musashi was already a legend in his own time, a man

considered by other Samurai to be invincible. He was also a man who

could have amassed a fortune, but instead rejected wealth in favor of

the more humble life of a teacher.

The Book of Five Rings, though thin and relatively uncomplicated,

is the kind of book that seems to transmit more meaning each time it is

read. |

"A leader should take into account abilities and limitations of his

men, circulating among them and asking nothing unreasonable. Know their

morale and spirit and encourage them when necessary."

Musashi also stresses adaptability and suggests that men should be like

water and "adopt the shape of its receptacle".

"In large scale the superior man will manage many subordinates

dextrously, bear himself correctly, govern the country and foster the

people," Musashi writes, "It is difficult to know yourself if you do not

know others."

To defeat an enemy, Musashi says, you must know him. "Become the enemy .

. . think yourself into the enemy's position."

"The important thing in strategy is to suppress the enemy's useful

actions, feign weakness. In large scale strategy, when the enemy starts

to collapse, you must pursue him without letting up. If you fail to take

advantage, the enemy will recover." |

|

|

|

|

A training text, used by a martial arts school to teach members of

the bushi (samurai) class, has been deciphered, revealing the rules

samurai were expected to follow and what it took to truly become a

master swordsman.

The text is called Bugei No Jo, which means "Introduction to Martial

Arts" and is dated to the 15th year of Tenpo (1844). Written for samurai

students about to learn Takenouchi-ryū, a martial arts system, it would

have prepared students for the challenges awaiting them. |

|

"These techniques of the sword, born in the age of the

gods, had been handed down through divine transmission. They form a

tradition revered by the world, but its magnificence manifests itself

only when one's knowledge is ripe," part of the text reads in

translation. "When [knowledge] is mature, the mind forgets about the

hand, the hand forgets about the sword," a level of skill that few

obtain and which requires a calm mind.

The text includes quotes written by ancient Chinese military masters and

is written in a formal kanbun style, a system that combines elements of

Japanese and Chinese writing. The text was originally published by

scholars in 1982, in its original language, in a volume of the book

"Nihon budo taikei." Recently, it was partly translated into English and

analyzed by Balázs Szabó, of the department of Japanese studies at

Loránd Eötvös University in Budapest, Hungary. The translation and

analysis are detailed in the most recent edition of the journal Acta

Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae.

Among its many teachings, the text tells students to show great

discipline and not to fear the enemy's numbers. "To see bad as good is

like stepping out of the gate we see the enemy, though numerous we see

them as few, therefore no fear awakes, so we triumph when the fighting

is just started," it reads in translation, quoting a teaching from the

Seven Military Classics of ancient China.

Last century of the Samurai In

1844, only members of the Samurai class were allowed to receive martial

arts training. This class was strictly hereditary and there was little

opportunity for non-samurai to join it.

|

|

A photograph taken around 1860

showing a Samurai in full armor with sword. Within two decades of this

photo being taken the Samurai would effectively be abolished and Japan

would move to a conscript army that would largely consist of peasants |

Samurai students, in most cases, would have

attended multiple martial arts schools and, in addition, would have been

taught "Chinese writing, Confucian classics and poetry in domain schools

or private academies," Szabó explained.

|

| The students starting their Takenouchi-ryū training in 1844 may not

have realized that they lived at a time when Japan was about to undergo

tremendous change. For two centuries, there had been tight restrictions

on Westerners entering Japan, something that would be shattered in 1853

when the U.S. commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay with a fleet

and demanded that Japan enter into a treaty with the United States. In

the two decades that followed, a series of events and wars erupted that

would see the downfall of the Japanese Shōgun, the rise of a new

modernized Japan and, ultimately, the end of the Samurai class. |

|

Samurai Rules

The newly translated text

sets out 12 rules that members of the Takenouchi-ryū school were

expected to follow. Some of them, including "Do not leave the path of

honor!" and "Do not commit shameful deeds!" were ethical rules samurai

were expected to follow.

One notable rule, "Do not let the school's teachings leak out!" was

created to protect the school's secret martial art techniques and aid

students should they find themselves in a fight.

"For a martial arts school … to be attractive, it was necessary to have

special techniques enabling the fighter to be effective even against a

much stronger opponent. These sophisticated techniques were the pride of

the school kept cautiously in secret, as their leaking out would have

caused economic as well as prestige loss," writes Szabó in his paper.

Two other, perhaps more surprising, rules, tell students "Do not

compete!" and "Do not tell bad things about other schools!" |

|

| Modern-day Westerners have a popular vision of the

samurai fighting each other regularly, but by 1844, they were not

allowed to duel each other at all, Szabó writes. |

This picture shows the hilt of a

Tachi (slung sword), dating to 1861, which would have been used by a

high-ranking young Samurai |

| The Shōgun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1646-1709) had placed a ban on

martial art dueling and had even rewritten the code the samurai had to

follow, adapting it for a period of relative peace. "Learning and

military skill, loyalty and filial piety, must be promoted, and the

rules of decorum must be properly enforced."

Secret Skills

The text offers only a faint glimpse at the secret

techniques the students would have learned at this school, separating

the descriptions into two parts called "Deepest Secrets of Fistfight"

and "Deepest Secrets of Fencing."

One section of secret fistfight techniques is called Shinsei no daiji,

which translates as "divine techniques," indicating that such techniques

were considered the most powerful. Intriguingly, a section of secret

fencing techniques is listed as Ōryūken, also known as iju ichinin,

meaning those "considered to be given to one person" — in this case, the

headmaster's heir.

The lack of details describing what these techniques looked like in

practice is not surprising, Szabó said. The headmasters had their

reasons for the cryptic language and rule of secrecy, he added. Not only

would they have protected the school's prestige, and students' chances

in a fight, but they helped "maintain a mystical atmosphere around the

school," something important to a people who held the study of martial

arts in high esteem. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Samurai Helmet |

Samurai Suit |

|

Kawarikabuto Helmet |

Samurai Clothing |

Lacquered Bowl . . . circa early

17th Century

Crests of two of Japan's Greatest Families — the Tokugawa and Mori |

|

Long Sword (Katana) Blade and Scabbard . . . circa

18th to 19th Century (top blade)

Short Sword (Wakizashi) Blade and Scabbard . . . from the late 18th to

early 19th Century (bottom blade) |

|