| |

Spartacus was a Thracian from the nomadic tribes and not only had a

great spirit and great physical strength, but was, much more than one

would expect from his condition, most intelligent and cultured, being

more like a Greek than a Thracian.

Plutarch, Life of Crassus |

| Spartacus was the leader of a rebellion of slaves and gladiators

which rapidly escalated into a full-scale war, the Third Servile War, in

the years 73-70 BC. Two traditional sources: Plutarch of Chaeronea

describes this war in his "Life of Crassus", and one generation later,

Appian told the story in his "History of the Civil Wars". Both accounts

describe almost identically the same events in the same sequence.

Some refer to Spartacus Thracian tribe as the Maedi, which in historic

times occupied the area on the southwestern fringes of Thrace, present

day south western Bulgaria. Spartacus served in the Roman army, but later was taken

prisoner and sold as a gladiator. Plutarch also writes that Spartacus's

wife, a prophetess of the Maedi tribe, was enslaved with him. |

|

|

|

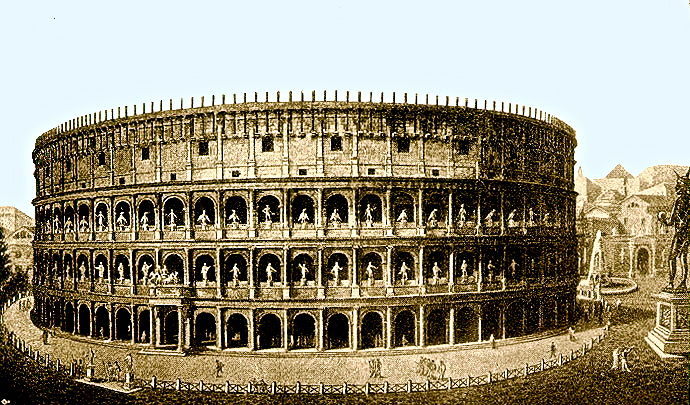

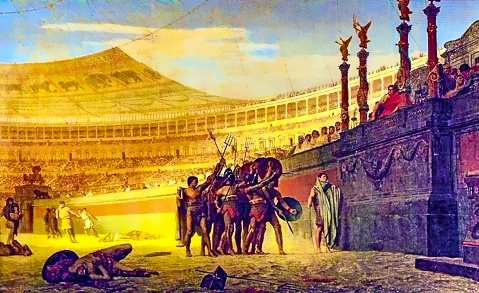

Combats between trained warriors

were first staged to

commemorate funerals in 264 BC, during the First Punic War. About one

hundred years later, 74 gladiators fought during a period of three-days

as a special funeral ceremony for wealthy Romans. But, the first

officially sponsored gladiatorial games were first held nearly 70 years

later, and they were an instant success with the Roman public. |

The Roman appetite for blood sports grew and thousands of prisoners

captured in Rome's numerous wars of conquest were carried off to

specially constructed training centers, or schools, called a Ludus, o

prepare them for the games.

The gladiators name originates from the Latin word Gladius, the short

sword favored by many of the combatants. Early gladiators were outfitted

with an ornately wrought visored helmet, a shield and an armored sleeve

worn on the right arm, after the fashion of Samnite Warriors defeated by

Rome in the late 3rd century BC.

A number of gladiator training schools sprang up throughout Italy,

concentrated near the town of Capua, north of present-day Naples. At

such schools, gladiators received training in a variety of weapons,

though they usually specialized in one. Diets were carefully observed,

and a strict exercise regimen was maintained. Discipline and punishment

were harsh.It was the influx of barbarian peoples into the Roman

Empire that ultimately ended the popularity of the gladiator contests.

About 404 AD the Emperor Honorius banned the games. |

|

|

Ancient Rome |

The Italian cities were rapidly growing. The countryside

also changed. Gradually, the small farms were displaced by large

plantations, where the work was done by

slaves, who could not be

recruited for military service. The Greek historian Appian of Alexandria

(95AD - 165AD) describes the results below.

"The rich used persuasion or force to buy or seize

property which adjoined their own, or any other smallholdings belonging

to poor men, and came to operate great ranches instead of single farms.

They employed slave hands and shepherds on these estates to avoid having

free men dragged off the land to serve in the army. |

| They derived great profit from this form of ownership too, as the

slaves had many children and no liability to military service and their

numbers increased freely. For these reasons the powerful were becoming

extremely rich, and the number of slaves in the country was reaching

large proportions, while the Italian people were suffering from

depopulation and a shortage of men, worn down as they were by poverty

and taxes and military service. And if they had any respite from these

tribulations, they had no employment, because the land was owned by the

rich who used slave farm workers instead of free men." |

|

In 73 BC, seventy-eight gladiators managed to escape from the

fighting school of Gnaeus Lentulus Batiatus at Capua. According to

Plutarch, they were only armed with choppers and spits, which they had

found in a kitchen. However, they soon discovered a transport of

gladiatorial weapons. From now on, they were heavily armed, and they

occupied a mountain.

Appian informs us that this was Mount Vesuvius itself, and that the

gladiators elected three leaders: Spartacus, Oenomaus and Crixus.

Probably they represented ethnic groups: a Thracian, a Greek, and a

German, according to Plutarch. At Vesuvius they were joined by hundreds

of other slaves, fugitives, and refugees from throughout Italy. Many of

the lieutenants were fellow gladiators and there were many well trained

fighting men among the ranks, as well as criminals and brigands.

The response of the Roman Senate was hindered by the absence of Roman

legions, which were already engaged in fighting a revolt in Spain and

simultaneously, the Third Mithridatic War. The Senate considered the

revolt a police action, not a full scale war and sent the Propraetor

Gaius Claudius Glaber with an army of 3,000 hastily conscripted and

untrained soldiers.The Propraetor had a small and untrained army, but

besieged the slaves on the mountain, hoping that starvation would force

them to surrender. The besieged instead made ladders from the branches

of vines, descended from the hill during the night, and attacked the

Roman camp in the rear. The Romans taken by surprise panicked and fled,

many were killed.

The Roman Senate launched a second expedition against the gladiators,

this time commanded by the Praetor Publius Varinius. He unwisely divided

his forces, and the Romans were thereby easily defeated. Spartacus men

nearly captured the praetor Varinius himself, who lost the very horse

that he rode. Captured legionaries were forced to fight each other as

gladiators or were crucified, just as some Romans crucified captured

slaves. |

| With success more and more slaves flocked to Spartacus, as did many

of the displaced herdsmen and shepherds of the region, swelling the

ranks to some 70,000 or more. But the revolt then splits, separating

into ranks according to their languages and electing their own

designated leaders. Taking as many as 30,000 men, including a contingent

of German and Gallic gladiators, the Gaul Crixus broke with Spartacus to

plunder neighboring villages and towns. The coming year, 72 BC, the

senate recognized the Spartacus rebellion as the 'Third Servile War".

The senators ordered both consuls, Lucius Gellius Publicola and Gnaeus

Cornelius Lentulus, to proceed against the bands of Spartacus.

But it was the Praetor Arrius, the newly appointed governor of Sicily en

route to his province, who met up with Crixus at Mt. Garganus. With

3,000 Germanics split from the main force of Spartacus, Crixus and his

small army were rounded up and utterly destroyed.

The deployed two Roman Legions of Consul Gneaus Cornelius Lentulus

barred the gladiator's path, while Consul Lucius Gellius Publicola

pursued with two Roman Legions, planning to crush Spartacus between

them. Spartacus had little choice but to continue marching right

into Lentulus, and did so with devastating effect. Afterwards, Spartacus

turned and utterly defeated the Legions of Gellius too. Continuing to

march north, the Spartacus slave army then met with the Proconsular

governor of Cisalpine Gaul, Cassius Longinus. Once again Spartacus

defeated the Roman forces in battle. |

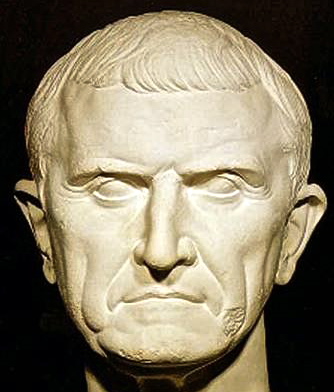

| The Propraetor Marcus Licinius Crassus was appointed to supreme

military command, as he was the only man who offered to accept the

position. Spartacus was now considered a serious threat and Crassus

commanded 6 new legions, and also four remaining veteran legions.

Crassus ordered his lieutenant Mummius to lead two of the new legions

behind Spartacus slave army, but as Plutarch notes, not to join battle

nor even skirmish with them. Mummius unwisely attacked the gladiators

from the rear, probably thinking he would have the advantage of

surprise. In the following battle, many of the legionaries were slain,

and many of the others broke and fled.

Crassus was angered by the disregard of his orders and the legionaries

cowardice. Mummius' decimated legions stood for their discipline before

him. Crassus ordered the seldom used penalty of decimation. Lots were

drawn in each group, with one unlucky soldier chosen for execution. In

this punishment, one of every ten men is beaten to death by their own

fellow legionaries. The entire army witnessed the deaths of their

comrades as warning.

The end of 72 BC, and Spartacus was encamped at the Strait of

Messina. Spartacus is there betrayed by Cilician Pirates and his plan to

transport a contingent of his slave army to Sicily by ships, is

thwarted. Spartacus has no choice except to keep on fighting.

In 71 BC, Crassus attempts to trap Spartacus and his slave army

at Calabria by building a ditch and a wall, nearly sixty kilometers long

and five meters wide across the 'toe' of Italy from sea to sea. |

Propraetor

Marcus Licinius Crassus |

| The plan was to contain the Spartacus slave army and cut off their

supplies. But Spartacus manages to break through the lines of defense

built by Crassus. While they did manage to escape, Spartacus lost a

tenth of his army, or nearly 12,000 men. Free from Crassus' siege,

Spartacus moved towards Brundisium, in the heel of Italy, where he still

hoped to secure escape by sea. The great general Pompey was just

returning from Spain, and the Roman Senate offered him an additional

command to put an end to Spartacus once and for all.

Unfortunately, Marcus Licinius Lucullus, fresh from a victory over

Mithridates in the east, landed at Brundisium with a full compliment of

legionaries. Spartacus had little choice but to face his pursuers. In

71 BC, the Spartacus slave army and the Romans under Crassus met in

war at Lucania, called the "Battle at the River Silarus". |

| In a document written by Appian of Alexandria, he stated that "The

fight was long, and bitterly contested, since so many tens of thousands

of men had no other hope. Spartacus was wounded in the thigh with a

spear and sank upon his knee, holding his shield in front of him and

contending in this way against his assailants until he and the great

mass of those with him were surrounded and slain". Soon after he fell in

battle, the rest of his rebel forces were cut to pieces. Over six

thousand were taken prisoner alive. They were crucified along the Via

Appia, the road between Rome and Capua. For years travelers were forced

to see the crosses. Every thirty or forty meters they saw the rotting

body of a former slave, prey for the vultures and dogs.

After savagely crucifying all of the insurgents taken in the war, the

Roman army found 3,000 unharmed and well tended prisoners in the camp of

the defeated rebel leader, Spartacus.

5,000 of the slave army manage to escape capture and flee north. But

they are met by General Pompey as he was returning from Spain, and

completely cut to pieces. |

|

| The body of

Spartacus is never found. Pompey claims credit for ending the

slave war and is granted a triumph. Crassus is given just an ovation.

The Spartacus rebellion was the last of the major slave insurrections

that Rome would experience. The fear engendered by the revolt, however,

would haunt the Roman psyche for centuries to come. |

|

|

|

|

|

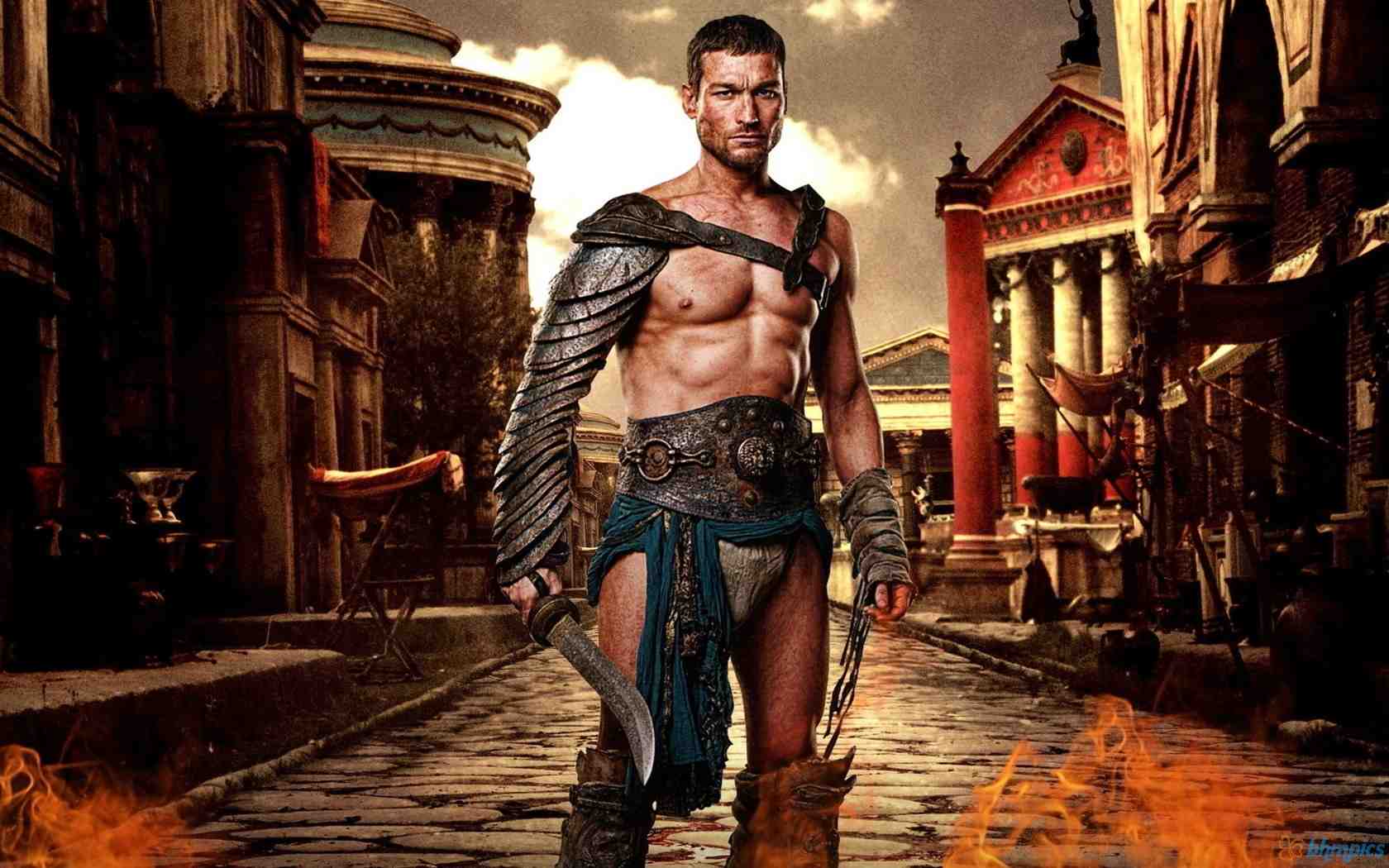

Spartacus - Starz Channel

Season One -"Blood and Sand"

Prequel - "Gods of the Arena"

Season Two - "Vengeance"

The upcoming third season of Starz's Spartacus will be its last

The premium cable network show will conclude with a

10-episode run titled

"War of the Damned", which will kick off in

January. Production is underway in New Zealand, with DeKnight already

having penned the series finale.

Spartacus stands as the first original scripted drama the network

developed in-house and has proved to be a valuable property for Starz,

with its most recent season -- Spartacus Vengeance -- averaging more

than 6 million viewers each week. In addition, the period drama that

featured the shocking deaths of six major characters including Lucy

Lawless' Lucretia in its Season 2 finale airs in more than 150 countries

worldwide.

Even after the show's first episode it was clear that

this is a most violent and bloody series. Limbs are severed in the

epically brutal final fight of the series premiere, a sliced neck pulses

with bright red blood, and the 300 style slow motion fixation on key

events ensures that every drop of ruby red liquid gets ample screen

time.

All of the major points of the classic story are there, but it’s not a

show about a story. It’s an orgy of blood, violence, and sex.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spartacus

The original Spartacus of Stanley Kubrick is definitely

more than just a historic movie. It is more than just an Oscar winning

picture and classic. Spartacus is a rare example of a masterpiece and

icon of cinematography from the 20th Century. This movie is a look

at life, history and philosophy.

Spartacus (Kirk Douglas) is a rebellious slave purchased

by Lentulus Batiatus (Peter Ustinov), owner of a school for gladiators.

For the entertainment of corrupt Roman senator Marcus Licinius Crassus

(Laurence Olivier), Batiatus' gladiators are to stage a fight to the

death. On the night before the event, the enslaved trainees are

"rewarded" with female companionship. Spartacus' companion for the

evening is Varinia (Jean Simmons), a slave from Brittania. When

Spartacus later learns that Varinia has been sold to Crassus, he leads

78 fellow gladiators in revolt. |

|

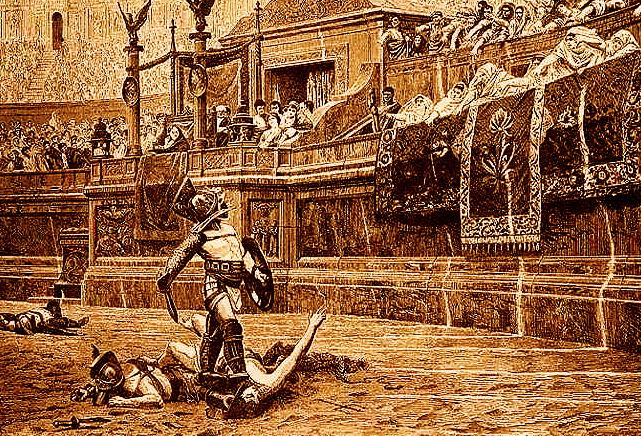

| The battle moments of the coliseum were made realistic – fast and

bloody. In comparison with the movie "Gladiator" (2001), it looks

harsher and simpler. In the Spartacus movie the main events are

accentuated on a theater of the open-air, battles and drama of a whole

epoch of Roman Empire, not just on the main hero, Spartacus. Spartacus

(1960) is a masterpiece, a commercial success, and an icon of cinema. |

|

|

|

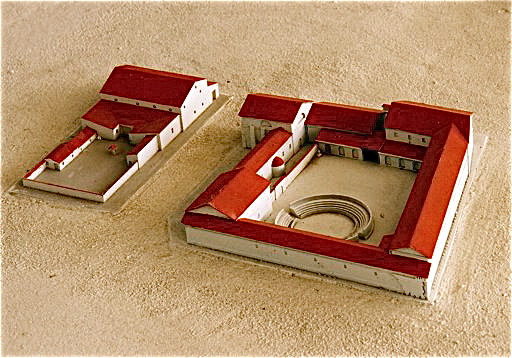

Unique Roman Gladiator School Unveiled in Austria

PETRONELL-CARNUNTUM, Austria — They lived in cells

barely big enough to turn around in and

usually fought until they died. This was the lot of those at a

sensational scientific discovery unveiled Monday: The well-preserved

ruins of a gladiator school in Austria.

The Carnuntum ruins are part of a city of 50,000 people 28 miles (45

kilometers) east of Vienna that flourished about 1,700 years ago, a

major military and trade outpost linking the far-flung Roman empire's

Asian boundaries to its central and northern European lands.

Mapped out by radar, the ruins of the gladiator school remain

underground. Yet officials say the find rivals the famous Ludus Magnus —

the largest of the gladiatorial training schools in Rome — in its

structure. And they say the Austrian site is even more detailed than the

well-known Roman ruin, down to the remains of a thick wooden post in the

middle of the training area, a mock enemy that young, desperate

gladiators hacked away at centuries ago. |

|

"(This is) a world sensation, in the true meaning of the

word," said Lower Austrian provincial Governor Erwin Proell. The

archaeological park Carnuntum said the ruins were "unique in the world

... in their completeness and dimension."

Digging at the city site began around 1870, but only 0.5 percent of the

settlement has been excavated, due to the enormity of what lies beneath

and to the painstaking process of restoring what already has been

unearthed.

Virtual video presentations of the former Carnuntum gladiator school

showed images of the ruins underground that morphed into what the

complex must have looked like in the third century. It was definitely a

school of hard knocks.

"A gladiator school was a mixture of a barracks and a prison, kind of a

high-security facility, The fighters were often convicted criminals,

prisoners-of-war, and usually slaves." Still, there were some perks for

the men who sweated and bled for what they hoped would

at least be a few brief moments of glory before their demise. |

|

|

Long Brutal Days

At the end of a dusty and bruising day, they could pamper their

bodies in baths with hot, cold and lukewarm water. And hearty meals of

meat, grains and cereals were plentiful for the men who burned thousands

of calories in battle each day for the entertainment of others.

Thick walls surround 11,000 square meters (13,160 sq. yards) of the

site, and the school and its adjacent buildings stretch over 2,800

square meters ((3,350 square yards).

Inside, a courtyard was ringed by living quarters and other buildings

and contained a round, 19-square meter (23-square yard) training area —

a small stadium overlooked by wooden seats and the terrace of the chief

trainer.

The complex also contained about 40 tiny sleeping cells for the

gladiators; a large bathing area; a training hall with heated floors and

assorted administrative buildings.

Outside

the walls, radar scans show what archeologists believe was a cemetery

for those killed during training.

The institute said the training area was where the men's "market value

and in end effect their fate" was decided. At the same time, it gave

them a small chance for survival, fame, and possibly liberty.

"If they were successful, they had a chance to advance to 'superstar'

status — and maybe even achieve freedom," said Carnuntum park head

Franz Humer. |

|

|

|

|

Roman Gladiators Ate a

Mostly Vegetarian Diet and Drank a Tonic of Ashes after Training |

|

These are the findings of anthropological

investigations carried out on bones of warriors found in the

ancient city of Ephesos |

|

|

In a study by the Department of Forensic Medicine at the

MedUni Vienna in cooperation with the Department of Anthropology

at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Bern,

bones were examined from a gladiator cemetery uncovered in 1993

which dates back to the 2nd or 3rd century BC in the then Roman

city of Ephesos (now in modern-day Turkey). At the time, Ephesos

was the capital of the Roman province of Asia and had over

200,000 inhabitants. Historic sources report that gladiators

had their own diet. This comprised beans and grains.

Contemporary reports referred to them as "hordearii" ("barley

eaters"). The result shows that gladiators mostly ate a

vegetarian diet. There is virtually no difference in terms of

nutrition from the local "normal population". Meals consisted

primarily of grain and meat-free meals. The word "barley eater"

relates in this case to the fact that gladiators were probably

given grain of an inferior quality. |

| Using spectroscopy, stable isotope ratios (carbon, nitrogen

and sulphur) were investigated in the collagen of the bones,

along with the ratio of strontium to calcium in the bone

mineral. |

|

Build-up Drink Following

Physical Exertion

The difference between gladiators and the normal

population is highly significant in terms of the amount of

strontium measured in their bones. This leads to the conclusion

that the gladiators had a higher intake of minerals from a

strontium-rich source of calcium. The ash drink quoted in

literature probably really did exist. "Plant ashes were

evidently consumed to fortify the body after physical exertion

and to promote better bone healing," explains study leader

Fabian Kanz from the Department of Forensic Medicine at the

MedUni Vienna. "Things were similar then to what we do today -

we take magnesium and calcium (in the form of effervescent

tablets, for example) following physical exertion." Calcium is

essential for bone building and usually occurs primarily in milk

products.

A further research project is looking at the migration of

gladiators, who often came from different parts of the Roman

Empire to Ephesos. The researchers are hoping that comparison of

the bone data from gladiators with that of the local fauna will

yield a number of differences. |

|

|

|

|

Gladiator Fights Revealed in Ancient

Graffiti |

|

Hundreds of Graffiti Messages

Engraved into Stone in the Ancient City of Aphrodisias Turkey

Discovered and Deciphered - Revealing what Life was Like over 1,500

years ago |

|

The Graffiti Touches on many Aspects of the City's

Life

Including Gladiator Combat, Chariot Racing, Religious Fighting and Sex

The Markings date to a Time when the Roman and Byzantine Empires ruled

over the City |

|

1025 AD - Byzantine Empire stretched across Turkey,

Greece and the Balkans |

| Graffiti are the products of instantaneous situations, often

creatures of the night, scratched by people amused, excited, agitated,

perhaps drunk. This is why they are hard to interpret. But this is also

why they are so valuable. They are records of voices and feelings on

stone. |

|

Most of the graffiti dates between roughly 350 AD and 500 AD,

appearing to decline around the time Justinian became Emperor of the

Byzantine Empire, in 527 AD.

Religion was depicted in the city's graffiti by Christians, Jews and

philosophically educated followers of the Polytheistic Religions.

In the decades that followed, Justinian restricted or banned

polytheistic and Jewish practices. Aphrodisias, which had been named

after the goddess Aphrodite, was renamed Stauropolis. Polytheistic and

Jewish imagery, including some of the graffiti, was destroyed.

But while the city was abandoned in the seventh century, the graffiti

left by the people remains today. Through the graffiti, the petrified

voices and feelings of the Aphrodisians still reach us. |

|

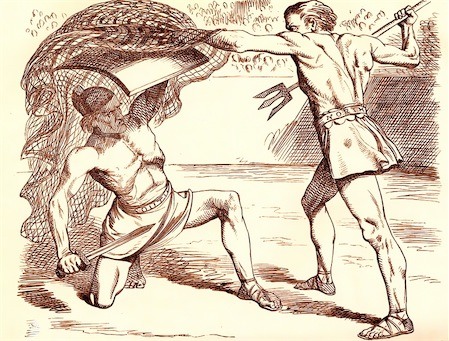

Graffiti in the Ancient City of Aphrodisias

Shows Gladiator Fights between a Retiarius (Gladiator

armed with a Trident and Net)

Versus a Secutor (Gladiator equipped with a Sword and Shield) |

Some of the most interesting gladiator graffiti was found on a

plaque in the city's stadium where gladiator fights took place. The

plaque depicts battles between two combatants (photo above).

One scene on the plaque shows the retiarius emerging victorious, holding

a trident over his head, the weapon pointed toward the wounded secutor.

On the same plaque, another scene shows the secutor chasing a fleeing

retiarius. Still another image shows the two types of gladiators locked

in combat, a referee overseeing the fight.

Probably a spectator has sketched scenes he had seen in the arena. The

images offer an insight into the perspective of the contemporary

spectator. The man who went to the arena in order to experience the

thrill and joy of watching, from a safe distance, other people die. |

|

|

The graffiti includes many depictions of gladiators. Although the

city was part of the Roman Empire, the people of Aphrodisias mainly

spoke Greek. The graffiti is evidence that people living in

Greek-speaking cities embraced gladiator fighting.

Pictorial graffiti connected with gladiatorial combat are very numerous.

And this abundance of images leaves little doubt about the great

popularity of the most brutal contribution of the Romans to the culture

of the Greek east. |

Chariot racing is another popular subject in the graffiti. The city

had three chariot-racing clubs competing against each other, records

show.

The south market, which included a public park with a pool and

porticoes, was a popular place for chariot-racing fans to hang out the

graffiti shows. It may be where the clubhouses of the factions of the

hippodrome were located; the reds, the greens, and the blues, referring

to the names of the different racing clubs.

The graffiti includes boastful messages after a club won and

lamentations when a club was having a bad time. "Victory for the red,"

reads one graffiti; "bad years for the greens," says another; "the

fortune of the blues prevails," reads a third. |

|

|

|