| |

|

Eastern China

Ancestor Ceremony Commemorates Lao Tzu |

|

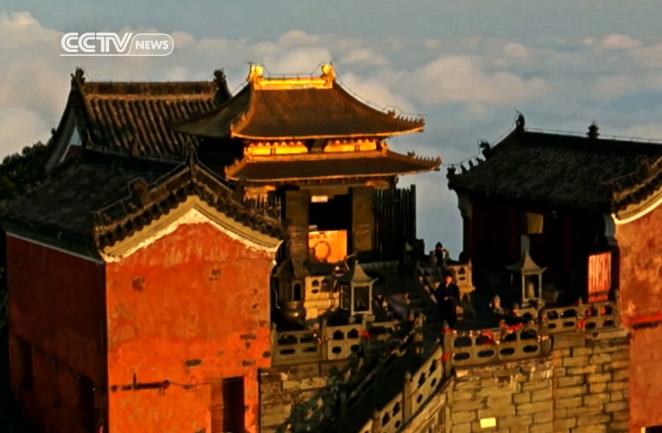

Ceremony held at Tianjing Palace

Commemorates Lao Tzu one of China's most Celebrated Philosophers

Lao Tzu lived during the 'Spring and Autumn Period' (770-476 BC) |

|

Lao Tzu's Birthplace - Guoyang

County of Bozhou City

East China's Anhui Province - March 26, 2017 |

|

Dressed in Traditional Han Clothing

Hundreds of Taoists 'Pay Respect to Lao Tzu' the Founder of

Taoism |

|

This Ceremony also marks the start

of the 'Seminar on Lao Tzu and Taoism Culture'

Attended by more than 1,000 Scholars and Taoists from both China

and Abroad |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lao Tze (BC 571-471) is the founder of Taoism and the author of the

Tao Te Ching, which details topics ranging from political advice to

practical wisdom.

Teachers at the academy will use the Tao Te Ching, the universal Taoist

text book written by Lao Tze more than 2,000 years ago, as the main

teaching material, said Zhou Fan, president of Guangdong Langdun Group,

investor of the project.

The academy, to be built in the Greater Toronto Area, will help further

spread the Chinese culture and allow the world to understand China in a

better way, Zhou told a press conference on Tuesday.

"We will pump 200 million yuan (32.02 million U.S. dollars) in building

the academy as well as a Lao Tze Garden there, which will cover an area

of 455 mu (0.3 square km)," Zhou said. |

|

Jiangxi Hosted the 3rd International Taoist Forum |

China hosted the Third International Taoist Forum in Yingtan, Jiangxi province, to push forward Taoist learning

and practice, the country's Taoist association announced.

The forum, held on Nov 25th & 26th,

2014 at Longhu Mountain,

was attended by close to 180 Taoist experts and

practitioners from more than 20 countries. The forum had the theme of practicing Taosim and

setting up moral role models, benefiting the people and

society, and included meetings on topics ranging from health

through environmental protection.

The forum helped

display the unique charm of Taoism and further promote the

Chinese traditional culture.

It also helped increase the impact of Chinese Taoism

worldwide and enhance international exchanges on the

subject.

The forum used new media, including micro blogs and

websites, to better connect with the audience. It also had

three televised forums.

Hu Youtao, vice-governor of Jiangxi province and director of

the organizing committee of the forum in Jiangxi province,

said it was held in accordance with standards of

international forums and observed official frugality rules.

The Tao of Health:

International Forum Focuses on Health and Longevity

Health and longevity have been the focus of

the 3rd International Taoist Forum in Southeast China’s

Jiangxi Province. In Taoist theory, to concentrate on

individual development is to practice the path of the return

to the Tao on a macro level to be in harmony with nature.

CCTV’s Han Bin interviewed Taoist masters to seek the

answers of healthy living.

Taoism is connected with achieving

well-being. Traditionally, those practices were reserved for

followers, acquiring an aura of mystery.

“To cultivate health, you need to learn the true meaning of

life. Only by understanding life, can we pursue the

cultivation of longevity, the importance of health,” said

Taoist master Zhu Heting.

“Health needs a healthy mind first, by minimizing your

desires and centering ourselves on stillness. Human lives

are in our control,” said Taoist master Li Zhiwang.

Taoism believes in the value of life. Taoists do not focus

on life after death, but rather emphasize practical methods

of cultivating health to achieve longevity. The forum only

gives a glimpse of their health philosophy to determine our

lies through the many meanings of Tao.

The First and Second

Taoist Forums were Held

Xi'an and Hong Kong, in 2007

Nanyue, Hunan Province, in 2011

|

|

|

|

|

|

The prodigious "Norton Anthology of

World Religions"

Taoism is listed as one of the six major living World Religions

With Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism |

|

Taoism is a Chinese belief tradition known to most

people in the West through the slim book “The Scripture of the Way

and Its Virtue”

(Tao Te Ching or, more correctly pronounced “Daode Jing”).

Attributed to a Sage in the 6th century BC named Laozi (often

spelled Lao Tzu). |

|

The “Daode Jing” has been called the most widely

translated book after the Bible

It teaches an enigmatic philosophy of living in harmony with nature and

achieving a kind of effortless success in life

by following the Dao, or the “Way” |

|

Taoist sensibility has infused pop culture, from the

Force in “Star Wars” to the best-selling “The Tao of Pooh.” But it’s

just one early work associated with Daoism, a far broader tradition that

includes teachings on celestial deities, alchemy, meditation, bodily

self-cultivation, and monasticism. Western thinkers have historically

focused more on Daoism’s philosophical than its religious side; in China

and other East Asian countries, however, Daoist ceremonies and rituals

are still important, though they were suppressed to some extent by the

Chinese Communist Party.

James Robson, a scholar of East Asian religions at Harvard, was tapped

to edit the Daoism section of the new Norton anthology, which meant

collecting a set of readings to define a tradition that has been notably

hard to pin down. He was able to draw on a recent resurgence of interest

among scholars who are translating and studying the surprisingly vast

Daoist religious canon, much of which had been lost and then

rediscovered in the 20th century.

Some might expect that a Harvard professor would enforce a purist

version of historical Daoism, but Robson took quite the opposite

approach. It includes religious texts, and also embraces writings by

Westerners intrigued by Daoist thought, including Carl Jung, Oscar

Wilde, and RZA, leader of the hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan.

Robson spoke in an interview from his office at

Harvard

IDEAS: Why should Daoism be considered a major living

religion?

ROBSON: I think most general readers would assume that Daoism and most

religion had died in China after the Cultural Revolution, because it had

been critiqued and dismantled and attacked. But in fact, what we find is

that it survived, and there’s been an incredible resurgence of the

tradition in China, and that it never actually went anywhere despite all

that it suffered. |

|

IDEAS: What did it suffer?

ROBSON: The persecutions of religion go all the way back to the late

19th century....China had gone through tumultuous times historically,

was perceived to be weak in relation to other parts of the world, and

had seen the success of science developing in other places, and

therefore anything that was religious or superstitious was considered to

keep China behind....They basically started to transform Daoist schools

and temples, and they dismantled the religious institutions, defrocked

the priests.

IDEAS: What about Daoism as a religion now?

ROBSON: Daoism has always knit together communities; it’s always been

the glue that’s held together local society, and it still does that

today....[In addition], you have this huge influx now of capital coming

back from wealthy overseas Chinese businesses that have led to the

revival and rebuilding of temples in China.IDEAS: Westerners seem to

have a fairly narrow view of Daoism, if they think about it at all.

ROBSON: One of the reasons Daoism was less well known to people around

the world, in comparison to, say, Buddhism and Hinduism in Asia, is that

the scholarship on Daoism is very new. It really only began in earnest

around the 1950s. There are two reasons. One is ideological; The

religious forms of Daoism were always perceived to be something less

than its philosophy....The other one is something more particular, that

the main body of Daoist texts, something like 60 major volumes that

constitute the Daoist canon, had gone almost completely out of

existence. There were one or two surviving copies in China, and those

were only rediscovered and printed in 1926.

IDEAS: In addition to these religious texts, you include an excerpt

from “The Wu-Tang Manual” and “The Tao of Physics,” among other

surprises.

ROBSON: It’s a world religion, in the sense that it spread to Korea,

Japan, to peninsular Malaysia, and then to Europe, the US, and

elsewhere. |

|

| I’ve tried to track that with a few key examples. I include a fair

amount of material on the Jesuits, who were the first ones to really

export knowledge of Daoism during the 17th and 18th centuries. But then

why stop there? So I include Alfred, Lord Tennyson...and Oscar Wilde,

who read a review of a translation of a Daoist text and was excited

about it. I include the Beatles, who took one chapter of the “Daode jing”

that was translated and put it to music. And the more recent one is

RZA’s own interaction with Daoism, where he read the “Daode jing” and

was incredibly moved by it, and that became an inspiration for him going

to China and also using the Wu-Tang—it should be pronounced “Wudang,”

because it’s the name of a Daoist sacred mountain that he took for their

band name. IDEAS: But doesn’t that risk just becoming a collection of

misinterpretations by outsiders? Where do you draw the line?

ROBSON: I don’t think there is one authentic Daoism; Daoism is many

different things to many different people over time, and what I tried to

do is explore the range of what that name has been applied to.

IDEAS: It’s fascinating that the “Daode jing” is so widely translated,

but you point out that many “translations” are by people who don’t even

read Chinese.

ROBSON: The “Daode jing” is a strange text in many ways....Everybody

thinks that Daoism has this transcultural nature to it that you can tap

into, and that if you read different English or French translations of

it, you can discern the meaning behind the text and write an “inspired

version.”...The occultist Aleister Crowley in the early 1900s did a very

bizarre thing where he retreated to this island in the middle of the

Hudson River, and then had a celestial vision where deities came down to

him and spoke the “Daode jing” to him...and that was his translation. He

basically said that Jewish Kabbalists gave him the key to understanding

the meaning of the “Daode jing.” And then Timothy Leary did [a]

“psychedelic translation” of the “Daode jing.”...People have this notion

that they can just sort of be in touch with the text and discern its

deepest meaning.

The irony is that some of those translations have been the best-selling

ones, and some of the most academically rigorous ones have not sold

anything. And the one that I would say is the most philologically

precise is absolutely unreadable. |

|

|