| |

|

Warrior's 3,900 Year Old Suit of

Bone Armour Unearthed in Omsk |

|

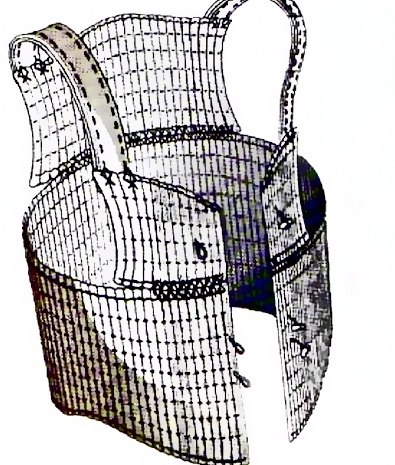

Archeologists are intrigued by the discovery of the

complete set of well-preserved Bone Armour which is seen as having

belonged to an Elite Warrior. The Armour was in perfect condition - and

in its era was "More Precious than Life", say experts. It was buried

separate from its owner and no other examples of such battle dress have

been found around Omsk. |

|

Nearby archeological finds are from the Krotov culture, who lived in

a forest steppe area of Western Siberia, but this bone armour more

closely resembles that of the Samus-Seyminskaya culture, which

originated in the area of the Altai Mountains, some 1,000 km to the

south east, and migrated to the Omsk area. The armour could have been a

gift, or an exchange, or was perhaps the spoils of war.

Boris Konikov, curator of excavations, said: 'It is unique first of all

because such armour was highly valued. It was more precious than life,

because it saved life.

'Secondly, it was found in a settlement, and this has never happened

before. There were found separate fragments in burials.

Currently the experts say they do not know which creature's bones were

used in making the armour. Found at a depth of 1.5 metres at a site of a

sanatorium where there are now plans to build a five star hotel, the

armour is now undergoing cleaning and restoration.

'We ourselves can not wait to see it, but at the moment it undergoing

restoration, which is a is long, painstaking process. As a result we

hope to reconstruct an exact copy', Boris Konikov said. |

Scientist Yury Gerasimov, a research fellow of the Omsk branch of

the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, said: 'While there is no

indication that the place of discovery of the armour was a place of

worship, it is very likely. Armour had great material value. There was

no sense to dig it in the ground or hide it for a long time - because

the fixings and the bones would be ruined.

'Such armour needs constant care. At the moment we can only fantasize -

who dug it into the ground and for what purpose. Was it some ritual or

sacrifice? We do not know yet.'

'Now we need to clean these small fragments of bone plates, make

photographs and sketches of their location, and then glue them in a full

plate.'

He is certain that the armour belonged to a "Hero", an "Elite Warrior

who knew special methods of battle" and would have given good protection

from weapons that were used at the time - bone and stone arrowheads,

bronze knives, spears tipped with bronze, and bronze axes.

The archeological site where the armour was found includes a complex of

monuments belonging to different epochs. There are settlements, burial

grounds, and manufacturing sites. Burials have been found here from the

Early Neolithic period to the Middle Ages.

The site is beside the Irtysh River. |

|

|

|

|

|

As woodlands expanded over much of Eastern Australia, Aboriginal

people in these areas adopted and relied on ground-edged stone hatchets

as a general purpose tool used for a variety of tasks: usage as a

weapon; to cut open the limbs of trees to get possums from hollows; to

split open trunks to get honey or grubs or the eggs of insects; to cut

off sheets of bark for huts or canoe; to cut down trees; to shape wood

into shields or clubs or spears; and, to butcher larger animals. The

importance of this tool to Aboriginal people in eastern Australia is

reflected by the fact there was at least one stone axe in every camp, in

every hunting or fighting party, and in every group travelling through

the bush.

The importance of ground edged stone hatchets was not confined to the

utilitarian; they were also valued trade items that extended the range

of social relationships well beyond the local group. Ethnographic

records indicate that such exchanges were usually embedded in the

regional network of prestige, marriage and ceremonial activity

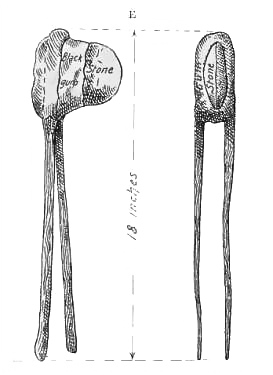

Ground-edge axes come in different shapes, but they are usually either

round or oval. They are sometimes rounded and narrow at one end, and

slightly broader and straighter at the cutting edge. Most are 50–200

millimeters long, 40–100 millimeters wide and 20–60 millimeters thick.

Typically they are ‘lens shaped’ when viewed from the side. |

|

| They were made from hard types of stone, particularly basalt or

greenstone, and worn river pebbles. They may have one or more ground

cutting edges, and they may be polished smooth all over. The ground

surfaces are usually highly polished. They may have a groove pecked

around their ‘waist’ so it is easier to attach a handle. |

While ground-edge stone hatchets can be produced from a range of raw

materials including river cobbles, the best raw materials occur in

relatively few places and material suitable for ground-edged hatchets

was extracted from specific quarry locations selected for the

suitability of the material for its use for cutting, scraping, pounding

and chopping.

A number of quarries used to obtain material for ground stone hatchet

head production are known. These include Moore Creek in northern New

South Wales, Lake Moondarra in Queensland Mount Camel in Victoria. There

are, however, only a few quarries that were intensively worked and the

stone hatchet heads from these quarries were traded over long distances.

The ground stone hatchet heads and the quarries from which they were

obtained are the product of social and technological adaptations by

Aboriginal people in response to the expansion of woodlands during the

late Holocene. |

Stone Grinding Tool |

| Although we do not know exactly when this started it must have been

sometime in the last 1,500 years, the period during which Aboriginal

people in south-east Australia used greenstone hatchets. |

Greenstone Axe Blank |

The Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry

William Buckley, an escaped convict living in the bush

from 1803 to 1833 provides the earliest European reference to the Mount

William Quarry, describing a hard, black stone from a place called Kar-keen

which was shaped into stone heads.

William von Blandowski, the first zoologist at the

Melbourne Museum, visited Mount William in 1854 and provides this

account of the quarry.

"The celebrated spot which supplies the natives with stone (phonolite)

for their tomohawks, and of which I had been informed by the tribes 400

miles distant. Having observed on the tops of these hills a multitude of

fragments of stones which appeared to have been broken artificially."

"Here I unexpectedly found the deserted quarries (kinohahm) of the

aboriginals." |

| "The quarries extend over an area of upwards of 100 acres . They are

situated midway between the territories of two friendly tribes, - the

Mount Macedon and Goulburn, - who are too weak to resist the invasion of

the more powerful tribes; many of whom, I was informed, travel hither

several hundred of miles in quest of this invaluable rock. The hostile

intruders, however, acknowledge and respect the rights of the owners,

and always meet them in peace" |

The Mount William stone hatchet quarry was an important source of

stone hatchet heads which were traded over a wide area of south-east

Australia.

The quarry area has evidence for both surface and underground mining,

with 268 pits and shafts, some several metres deep, where sub-surface

stone was quarried.

There are 34 discrete production areas providing evidence for the

shaping of stone into hatchet head blanks. Some of these areas contain

mounds of manufacturing debris up to 20 metres in diameter.

At Mount William, the number, size and depth of the quarry pits; the

number and size of flaking floors and associated debris; and the

distance over which hatchet heads were traded is outstanding for showing

the social and technological response by Aboriginal people to the

expansion of eastern Australian woodlands in the late Holocene.

Not all hatchet heads came from Mount William, although that quarry was

probably the most important in the region. Outcroppings of silcrete,

which was favoured for making small flaked implements, are known to

occur in the Keilor area and on the Mornington Peninsula.

Ground-edged Stone Hatchet |

Australian Aboriginal Stone Axes |

|

Ground-edged Stone Hatchet

Sturt Creek (Western Australia)

The head is of a very dark and hard green stone, ground

to a fine edge, and is set between the two arms of the handle and held

in place with spinifex gum. The handle is formed by bending round

(probably by means of fire) a single strip of wood. The two arms of the

handle are sometimes held together by a band of hair-string.

Source: Spinifex and Sand by David W. Carnegie A

Narrative of Five Years' Pioneering and Exploration in Western Ausralia

1892 |

|

|

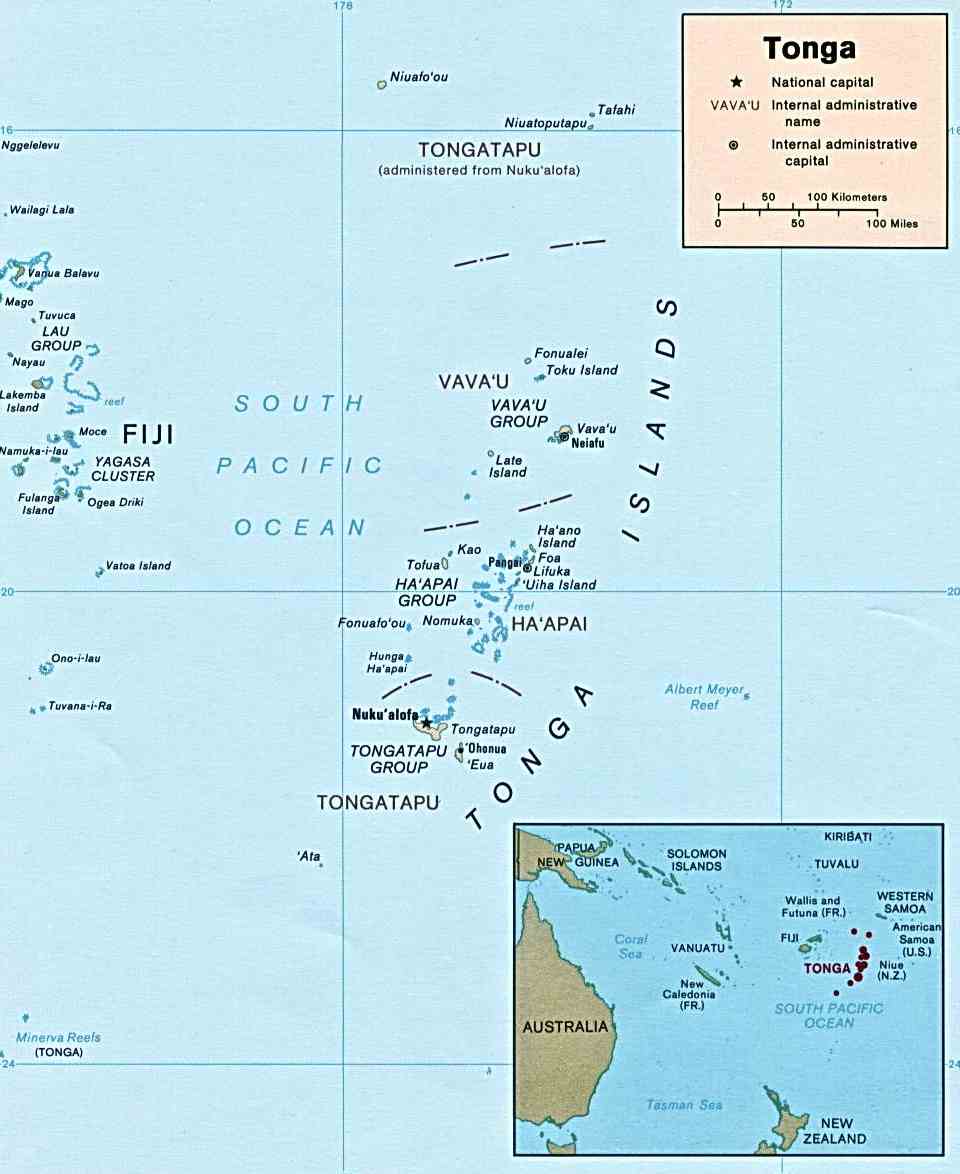

Pacific Oceanic Tongan War Clubs |

| Tongan clubs have been used throughout pre and post-contact times.

Prior to the introduction of iron materials by Captain Cook and other

sailors, sharks tooth, bone, and stone were used to etch designs onto

the clubs. However, after the introduction of iron materials such as

nails, club designs became very elaborate and decorative through the

ease of these tools. There are various types of clubs found throughout

Tonga. These clubs were used for warfare and traditional dance as in the

Me'etu'upaki.

In Western Polynesia, each island group developed a variety of styles

of long clubs made from ironwood (Casuarina equisetifolia). Many Tongan

clubs are elaborated with large areas of very skilful geometric

incising, frequently including small animal and human design motifs.

Other Tongan clubs are smooth-surfaced and have carved ivory, whalebone,

or pearl shell inlays usually in the form of circles, crescents and

stars, though other shapes are occasionally found. Fijians also use

inlay on some of their clubs, and it is thought that they adopted this

technique from the Tongan. It is likely that elaborately made clubs with

inlay, such as these, were ceremonial and served as badges of office

Tongan clubs can be differentiated from similar Fijian war club forms by

the presence of a lug for a wrist thong at the base of the butt. Tongan

clubs can be further differentiated from Samoan clubs, which also have a

lug, on the basis of lug form. In Samoan examples, the lugs are usually

triangular and occupy the entire width of the club base. In Tongan

clubs, these lugs are more often rectangular or arched and do not

traverse the width of the base. Sometimes Tongan weapons have holes

chiseled into the base for the attachment of wrist thongs |

|

| According to A. Mills Sainsbury Research Unit, University of East

Anglia Tongan club “Akau comprise roughly 20 percent of the Polynesian

art collected on the Captain James Cook voyages of the 1770s;

consequently, they are the single most numerous class of documented 18th

century Polynesian artwork, heavily outnumbering all other Tongan

artifacts” |

|

Tongan Club |

Tongan Club Detail |

Throwing Club |

Paddle Club |

There are several

categories of Tongan War Clubs

1) Kolo - The short throwing club

2) Povai - The pole club which can be compared to a baseball bat in

shape with the same flared rounded head

3) There is also a variation of the povai with a flattened top to the

clubhead

4) Apa'apai - The club with a diamond-sectioned flat-topped head

sometimes referred to as a coconut-stalk club, although it is the actual

coconut leaf midrib which is meant

5)There is also a type of apa'apai that is similar but with a head that

is more spatulate and rounded at the upper end like a paddle club

6) Moungalaulau - The paddle club with its rounded upper end was often

distinguished by finely carved decoration over its entire surface and

was sometimes found with and without a transverse ridged collar or cross

rib. |

|

The above pictures are close ups of the apa'apai

variety club. The designs are intricate and vary from club to club |

|